Taškas. A dot above an e

A shiny silver dot and the protection of a language; Agnieszka Nowakowska reports from Kaunas and the installation of a new artwork dedicated to the identity of a nation

Pic 1. The silver dot art installation in Students’ Square, Kaunas

On Saturday, 6th January 2024, a statue of a dot was unveiled at Students' Square in the centre of Kaunas. The dot is quite large, silver and shiny. The unveiling of the statue was attended by many people from Kaunas (let's appreciate the fact that they wanted to leave their homes: it was -9 degrees!) who were eager to take selfies with the dot. There were performances by musicians, lasers, speeches by the deputy mayor of Kaunas, the Lithuanian ambassador to the Czech Republic and the deputy head of the State Commission for the Lithuanian Language, among others. A dot that has lived to see its own statue and such a celebration must be extremely important!

Pic 2. The silver dot is etched with 15 words honouring the uniqueness of the Lithuanian culture

Of course, this is not an ordinary dot. It is a dot placed over the letter e in Lithuanian. It indicates that this vowel should be pronounced slightly longer and softer than the e without the dot. The Ė clearly indicates that this is a Lithuanian word – no other language has this letter in its alphabet. However, as we learn from the celebrities on stage, its existence is under threat, mainly from the use of new technologies. Lithuanians no longer dot the e when communicating via instant messaging, text messaging or email. It is easier and faster this way, and even without the dot, everyone will understand the message.

The creators of the monument unveiled in Kaunas wanted to highlight and celebrate the uniqueness of the Lithuanian language. The presenter of the ceremony reminds those gathered of the most important information about the Lithuanian language - that it is uniquely archaic and very similar to Sanskrit. Slogans about love for the language, which is the source of Lithuanian identity and strength, are heard from the stage. We hear that if the Lithuanian language ceases to exist, Lithuanians will also disappear. The silver dot, covered with fifteen words, including the extraordinary letter ė, is meant to honour this uniqueness of Lithuanian culture. To emphasise that it should be cared for and that modernity does not exclude care for the language.

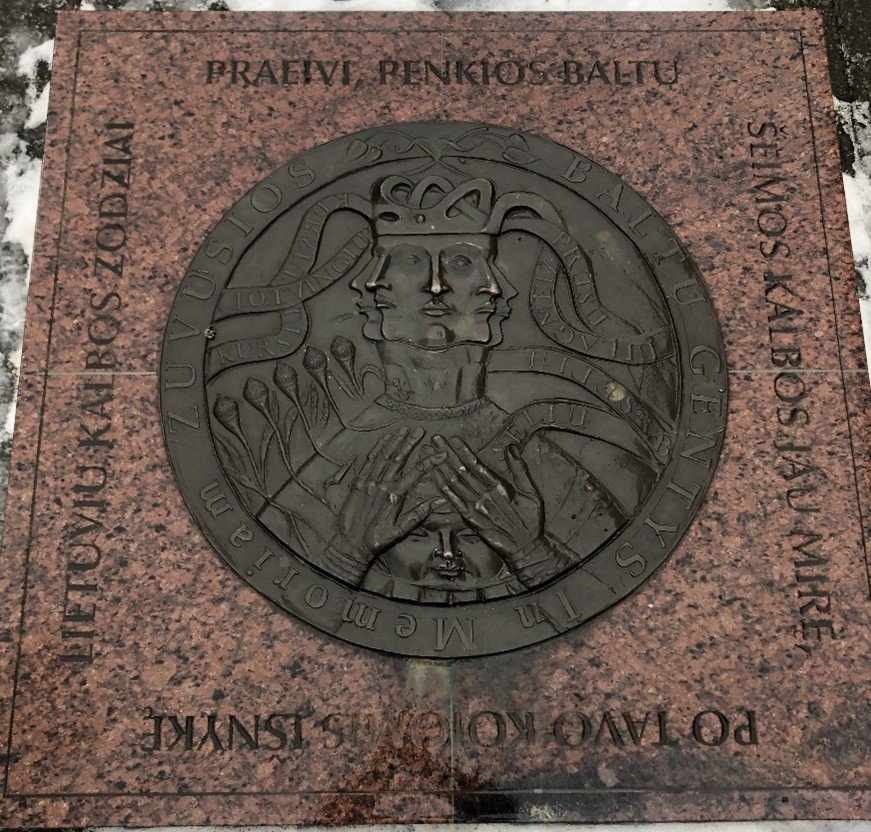

Pic 3. The 2013 "Monument to Language" in Klaipėda

This is not the only monument to language in Lithuania. In 2013, a "Monument to Language" was unveiled in Klaipėda with the inscription: "Passer-by, the five languages of the Baltic family have already died, under your feet are the Lithuanian words that have perished. Remember and honour your language". Next to it are boards with words from the Lithuanian language that have fallen out of use. They are meant to prove that the Lithuanian language is dying out and may cease to exist like the other Baltic languages - Old Prussian, Sudovian, Curonian, Semigallian and Selonian.

Along with Latvian, Lithuanian is one of the two Baltic languages still in use today. It is spoken by about 3.5-4 million people worldwide. These are mainly Lithuanians living in Lithuania and the Lithuanian diaspora in the USA and Canada. The number of speakers is steadily decreasing for demographic reasons. The monument in Klaipėda, though very different in form, carries a similar message to the silver dot in Kaunas: it is an appeal to care for the mother tongue, an expression of the fear of its disappearance. For Lithuanians, language is a symbol of national identity, a sense of belonging and separateness.

Pic 4. Monument to a book smuggler (lit. knygnešys), a symbol of the language struggle in the second half of the 19th century

The memory of the struggle for the Lithuanian language is visible in public space, even at a distance of several metres from the silver dot. The participants in this struggle are presented as heroes of national history. Not far from Vytautas the Great War Museum in Kaunas, there is a monument to the book smuggler (lit. knygnešys), a symbol of of the struggle for the language in the second half of the 19th century. In response to the Russian Empire's ban on printing Lithuanian books in the Latin alphabet (Lithuania was within its borders at the time), hundreds of people began smuggling such publications from abroad. The ban was seen as the first step towards the Russification and nationalisation of Lithuanians. It was lifted after 40 years, in 1904.

Among the busts of Lithuanian national heroes outside the War Museum are those of writers and linguists. Thanks to their efforts, Lithuanian survived Polonisation and Russification and became the language of literature and science. One of them is Jonas Basanavičius (1851-1927) - editor of Lithuanian-language magazines, reformer of Lithuanian orthography, politician and social activist.

Pic 5. Jonas Basanavičius (1851-1927) - an editor of Lithuanian-language magazines, reformer of Lithuanian orthography, politician and social activist

Since Lithuania regained its independence in 1990, the status of the Lithuanian language has been protected by legislation such as the Law on the State Language of the Republic of Lithuania and the Law on the Status of the State Language Commission. The exceptional importance of the Lithuanian language for Lithuanians has been a source of conflict with national minorities, especially Poles. It has also been a source of tension between the Lithuanian and Polish governments. Since 1996, a law has made it impossible to write forenames and surnames with letters that do not function in the Lithuanian alphabet (w, q, x). The Lithuanian law also made it impossible to write Polish names and surnames using letters characteristic of the Polish language, such as sz or cz. Polish names and surnames written in Lithuanian changed their appearance and, for example, my name Agnieszka Nowakowska would become Agnėška Novakovska. This seemed to be an insoluble conflict. The Lithuanian side stressed that by protecting the language they were protecting their identity. Representatives of the Polish minority pointed out that the legislation would lead to a distortion of their names and surnames, which are a basic element of identity. A partial change to the controversial rules was introduced on 1 May 2022, when names could be written with the letters w, q, x.

The ceremony to unveil the dot statue ended with a performance by singer Monika Marija. The songs are mostly in Lithuanian, but there are a few in English. This does not seem to bother those who celebrate the uniqueness of the Lithuanian language.

Dr Agnieszka Nowakowska is a sociologist and historian. She has conducted fieldwork in Poland and Lithuania. Her main interests are memory studies and sociology of education. Her PhD examined history teaching in Vilnius, and described the results of contact of official narratives about the past with everyday practices of memory.