From the West and the East to Lahore: Iqbal and Asad

The University of Warsaw’s Małgorzata Głowacka-Grajper goes in search of the legacy left by the first man to travel around the world on a Pakistani passport.

When teaching students at the University of Warsaw about national identity and national and religious conversions, I often recall the figure of Muhammad Asad – the first man to travel around the world with a Pakistani passport. He had come a long way in the literal and spiritual sense before he obtained his passport. He travelled around the world for years until in 1934 he reached Lahore in British India, where he met Muhammad Iqbal – a poet and philosopher who laid the ideological foundations for the creation of the state of Pakistan. Iqbal convinced him to end his travels, settle in Lahore and begin working to create an Islamic state.

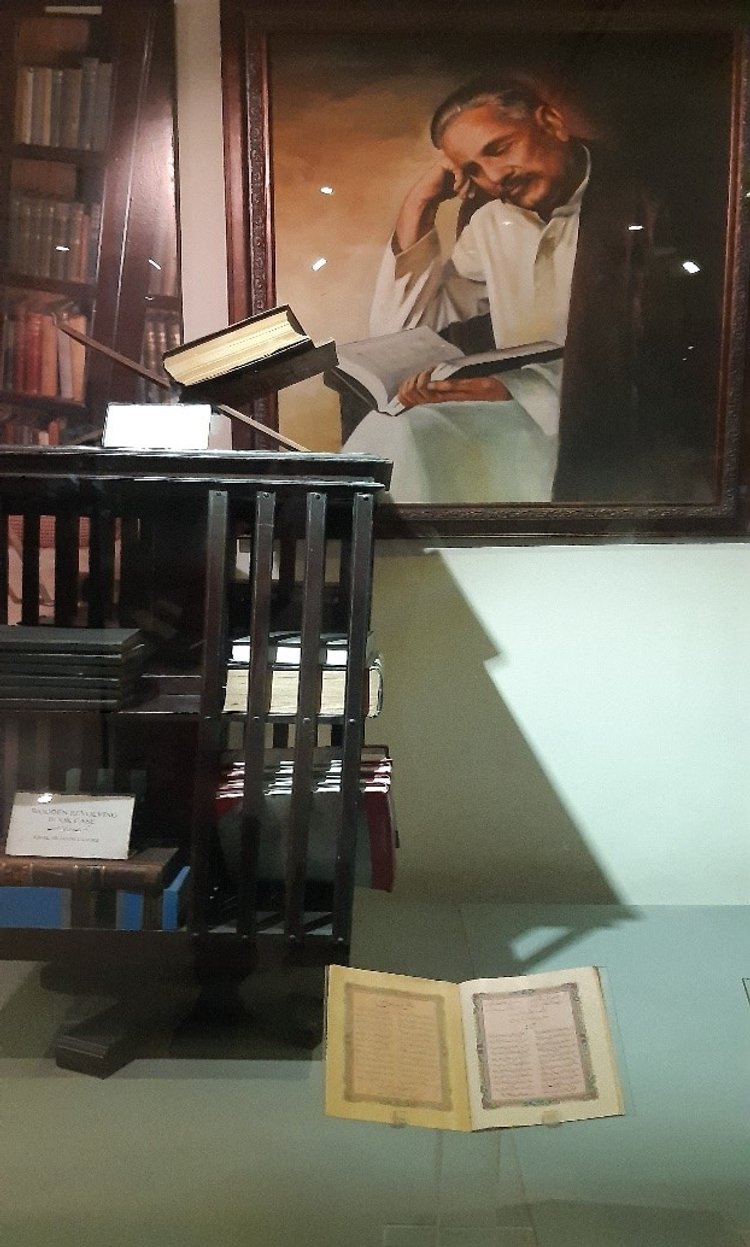

Pic 1. A display about Muhammad Iqbal in the Pakistan Monument Museum in Islamabad

While in Lahore, I looked for traces of Asad in historical museums. He’s nowhere to be found. However, in bookstores in this city, you can easily buy new editions of his most famous book from 1954, “The Road to Mecca”, which describes his life path leading to conversion from Judaism to Islam. On the contrary, Muhammad Iqbal always appears in museums dealing with the history of Pakistan. There is also his house museum in Lahore. Iqbal is constantly honoured and commemorated as the “ideological founding father” of Pakistan and as an outstanding Persian and Urdu poet. Asad is almost forgotten, and his idea of the League of Muslim Nations was never accepted. However, he is still recognised as the author of books and translator of the Quran into English. However, what is striking is that both thinkers were united not only by the idea of an Islamic state but also by thinking about the relations between the philosophy and culture of the West and the East.

Muhammad Asad was born Leopold Weiss in 1900 into a Jewish family in Lviv. Today it is one of the largest cities in Ukraine, but in the early 20th century it was a multicultural, mostly Polish-Jewish city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His parents were not very religious people, but, according to tradition, they sent young Leopold to study with a rabbi. Weiss's extraordinary linguistic talent quickly became apparent. His native languages were Polish and German, but he quickly also learnt Hebrew, Aramaic, English, French, Persian and Arabic. He moved to Vienna and then to Berlin, became a journalist and travelled through the Arabic world. He also visited British Mandatory Palestine where his uncle worked. Living there he became critical of Zionist ideology and started thinking about the rights of Muslims and their culture open for spiritual needs. In 1926, after experiencing illumination on the streets of Berlin, he converted to Islam. Then he left for Saudi Arabia and in 1934 came to British India where Iqbal convinced him to devote his life to building an Islamic state for Muslims on the subcontinent.

Like Asad, Iqbal had an extraordinary talent for languages. He knew Urdu, Punjabi, Persian, English and German. He completed his education at Cambridge, London and finally in Munich where he obtained his doctoral degree in philosophy. Works of Friedrich Nietzsche and Henri Bergson fascinated him as well as the poetry of Goethe and Heine. But not the materialism of European culture he experienced—the same for Asad who left European culture for Mecca in pursuit of spiritual harmony and balance.

Pic 2. Iqbal’s house is now a museum in Lahore

Iqbal noted: “The Western [way] enlightens the mind but spells ruins to the heart”. These words are highlighted in the museum as a way of thinking about Islamic culture and its relation to the West which was also close to the feelings of Asad. Coming from the East and the West they encountered in Lahore the possibility of building a new state. Iqbal died in 1938 and did not witness the creation of Pakistan in 1947. But Asad worked for the new state. Firstly, he joined the Department of Islamic Reconstruction and later the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as head of the Middle East Division. To establish relations with other Islamic countries he left on an official visit to Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Syria with the very first passport issued to a citizen of Pakistan. In 1952, he became Pakistan’s Minister Plenipotentiary to the United Nations in New York, but the same year quit to write the “Road to Mecca” and for a life with his new wife whom he met in New York. She was Pola Hamida Kazimirska – a Polish Roman catholic woman who converted to Islam in the United States. He found a person who shared with him the conversion experience from Central European culture to Islamic one. They spent the rest of his life together and the English translation of the Quran by Asad is dedicated to her. In 1983, he visited Pakistan for the last time. He was invited by President General Zia ul-Haq to Islamabad and was received with great honour. He managed also to visit his friends in Lahore for the last time. Asad died in 1992 in Spain and was buried in Cordoba – a place with a splendid mosque which Iqbal visited and described in his poem. Iqbal is buried in Lahore’s Walled City in the tomb near the Badshahi Mosque.

Many of Asad’s political ideas did not attract the politicians of Pakistan and he is absent in the official narrations on the founding of Pakistan in history museums of Islamabad as well as in Lahore. But he is still remembered by many as a bridge-builder between the West and Islam. His son Talal Asad grew up in Lahore where he finished Christian missionary school and left for studies in the United Kingdom. Now Professor Asad is a renowned anthropologist of religion and colonialism. While working in many universities in Great Britain, Sudan, Egypt, Saudia Arabia and the United States he developed his ideas on Orientalism and Eurocentrism in researching Islamic cultures and continued the work on mutual understanding between Islam and the West.

Dr Małgorzata Głowacka-Grajper is a sociologist and social anthropologist. Her main interests are contemporary developments in ethnic and national identity and problems of social memory and tradition. Małgorzata has conducted fieldwork in Poland, Lithuania, Slovakia and in the Siberian part of Russia. She has published several articles and books on ethnic minorities in Poland, ethnic identity and social memory in post-soviet countries and on the memory of resettlements. Currently she is working on the relationship between memory and religion in local communities and on Central Europe from a postcolonial perspective.