Where third-worldism meets agonism: what can we learn from, and with, each other?

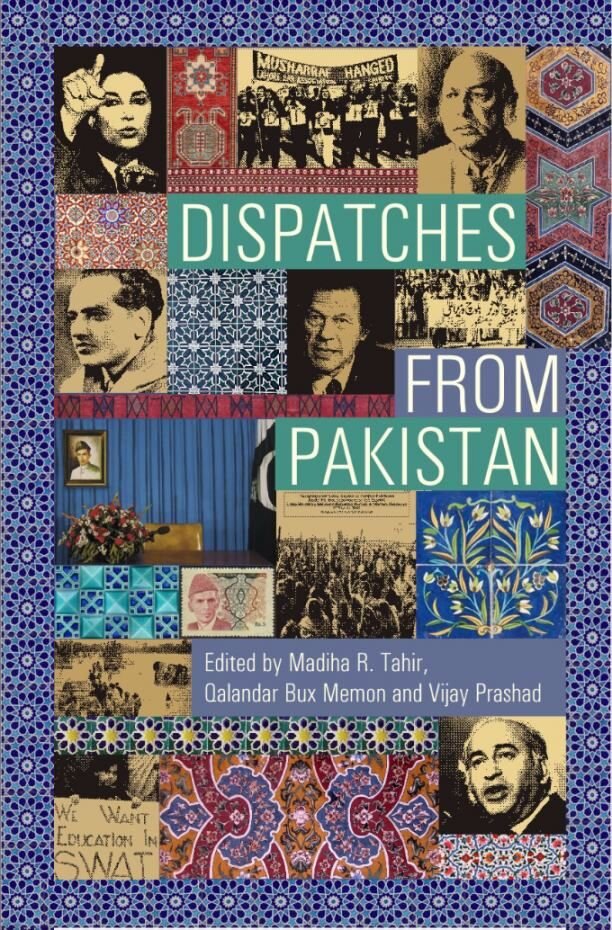

Qalandar Memon is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science of Forman Christian College in Lahore, Pakistan. He co-edited Dispatches From Pakistan (University of Minnesota Press) with Madiha Tahir and Vijay Prashad and is currently working on a book titled, People's History of Pakistan. In summer 2019 he spent a month on secondment to the University of Bath to undertake research as part of the DisTerrMem project. Here, he relates his work with communities in struggle in Pakistan to the aims and approaches of DisTerrMem as an EU-funded project, and considers a number of ethical questions.

South Asia: writing a ‘history from below’

My work for the past few years has been to engage in writing a ‘history from below’ with communities in struggle in South Asia. The partition of India in 1947 into two independent nation states, India and Pakistan, and the national ‘state-sponsored’ ideology that followed partition, swept aside the histories of many people. At partition we all became either Pakistani or Indian. Both entities are projected as ‘ontological’ realities: pre-existing entities that were awaiting a historical time to come into being. So ‘Pakistanis’ existed before Pakistan. This type of national discourse lays aside community and national history, and also other political identities and memories (such as claims to sovereignty or subjectivity). Epistemic violence of the state towards certain communities is invariably enforced by that state’s coercive apparatus. Within that context, my task has been to work with communities to document their history.

Ethics from a third worldist and decolonial standpoint

How does one engage with a community that’s the subject of state violence and is in resistance? This ethical question has pre-occupied my thoughts as much as my empirical work. I work with the oral history tradition but from a third worldist and a decolonial methodological standpoint. I’d like to make a few comments on this. Third worldists have never seen a gap between theory and practice. Central to third worldism is activism in dialogue with a community. Central texts of third worldism have developed from, and within, struggles. Key examples include Friere’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, Walter Rodney’s The Underdevelopment of Africa and CLR James’ The Black Jacobins (a book which could rightly be viewed as one of the first works of ‘history from below’). Third worldists aim to have a reciprocal (Friere calls this ‘dialogical’) relationship with the community they engage with, not only as people who document, but also who engage in, and take the risks of political activism with, the community.

Reflecting on such examples, the collection and analysis of data on communities in struggle, and the subject of state violence, raise various ethical questions. What is the researchers’ relationship with the research subjects? How should researchers engage with communities? For those of us in the third world, there’s another important question around what it means to circulate knowledge of communities in the third world for the metropole.

Solidarity and shared authority

In my practice I follow the tradition of third worldists to address these issues - though not necessarily always to overcome them. Two methods stand out. First, as already mentioned, one has to politically champion the community one has a relationship with and work with them dialogically. This can be done by showing solidarity with their cultural and political movements. Second, it is vital to open up one’s methods and work, and how that work is being used with the community. In the oral history tradition we term this ‘shared authority’. This requires that the history written by those of us trained and paid to work on such projects has to be reviewed and assessed by the community - they have to be made ‘co-authors’.

‘Third worldism’ meets agonism

In the summer of 2019 I spent a month on secondment to the University of Bath as part of the DisTerrMem project, in order to undertake collaborative research. I found it particularly interesting to take the above-mentioned modes with which I have been operating and examine them in the light of the proposed approach to the study of memory within DisTerrMem. This has been, and remains, a challenging task. The project draws on the agonistic approach to memory proposed by Cento Bull and Hansen (2016) draws on Chantal Mouffe’s definition of the political as an inherently conflictual realm, in which ‘opposed views, political passions and social imagination can compete and be democratically channelled through an adversarial dynamics of public contest and confrontation’ (more information can be found in the introduction to the DisTerrMem literature review).

During my time in Bath, I had time to think over the differences in my understanding between the two models. The third worldism-inspired history from below aims to ‘correct the historical record’ by enabling voices to be heard that would otherwise have been, or continue to be, suppressed. While agonistic and third worldist history from below deal with historical memory of communities in oppression, they do so in different ways. The question arises as how the two approaches can work together? And what each can learn from the other? These are the questions I will continue to investigate with great interest.

My experience of living and working in Bath, and of visiting Europe, also raised some questions. Given that the DisTerrMem project concerns itself with the historical memories of communities that are often in conflict or in exclusion, I was keen to look at and understand the EU from the standpoint of immigrants and people of colour. The decolonizing movement in the UK and across Europe has long argued that the historical memory of the colonized people is not allowed into the European cultural, political, academic and social framework. What European colonization did to the world, how it created Europe and how internal colonization has not been sufficiently addressed - the ‘hostile environment’ policy towards migrants in the UK provides one example. Such practices are possible in part because the historical experience of colonialism and the experience of people of colour has not been taken into account. How could the agonistic model be used to integrate communities of colour across Europe? To what extent do such communities consider themselves part of the political space? It is interesting to note that the Labour Party in the UK had it in its manifesto to begin such a process of accounting for the effects and impact of colonialism (across North Africa and the Middle East). As such, I used my time in Bath to begin to think about how I might study the experience of people of colour and will report further as the project progresses.

Qalandar Memon is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science of Forman Christian College in Lahore, Pakistan. He is also a writer, poet and was a founding editor of Naked Punch Review.

Discover more at www.disterrmem.eu/forman-christian-college