A brief reminder from the past

Inspired by visits to Warsaw‘s many wonderful museums, Tadas Šaulys from the Institute of Grand Duchy of Lithuania, reflects on troubling parallels with current conflicts.

Many nations which spread from the north to the south of Europe, from the Finns (who had some autonomy within the Russian Empire) to the Balkan nations, did not have their own statehood before World War I. As power shifted, the question of future borders naturally arose. Some of these issues were resolved more peacefully, some less so. A good example of both is the delimitation of the borders of Lithuania, which declared its independence in 1918. For example, the border with Latvia was settled by territorial exchange (Aknysta for Palanga), but the southern and south-eastern borders were not so smoothly defined. Poland's eastern borders moved back and forth with the front line in the Polish-Soviet war, and the border with Lithuania became an open point of dispute. This was eventually settled militarily, but great antagonism existed between the two countries until the end of World War II. World War II was followed by the redrawing of national borders and was 'sealed' by the mass deportation of populations; it seemed that the issue of borders would never arise again in this region.

For a typical Lithuanian used to going to Polish supermarkets, today there is no need to fear that every Polish person you meet will say "Litwo, Ojczyzno moja!" [Lithuania, my homeland] to you. We have come to see this saying as a reflection of our common historical past in the present, which does not pose a direct threat to the existence of the Republic of Lithuania, especially as relations between the two countries have recently improved again. However, we can also ask ourselves where this understanding of a common past has gone with the hysteria in Lithuania over the emergence of Litvinism from Belarus. One of the definitions of Litvinism is that the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL) was a Belarusian state, that the medieval Lithuanians (Litvins) were Belarusians, and that modern Lithuania is the result of a falsification of history and Vilnius should belong to them. We should realise that the Belarusian use of the GDL’s heritage is supposed to move them away from Moscow's influence, but paradoxically, this position encourages an inadequate reaction of rejection here in Lithuania, which pushes the Belarusian people towards Moscow. The paradoxical situation is that of Lithuania's northern border. Already after the inter-war amicable agreement with Latvia, it seemed that there would never be any disputes over this border. However, the paradox is that, after both countries joined the Schengen area and the land border practically ceased to exist, Lithuania and Latvia have still not ratified their maritime border treaty (almost 34 years after independence!). So, the most realistic territorial claims (apart from the threat of the Russian world) may arise where they were least expected.

In the 20th century, the borders of the countries belonging to the region known as Central-Eastern Europe moved so much (with the tiny exception of a stretch of the border established by the Treaty of Melnas - pl. Pokój melneński, ger. Friede von Melnosee - between the GDL and Teutonic Knights in 1422) and were subsequently resettled, that disputes over territories have become a thing of the past, but disputes over the past itself have remained and, in my opinion, will never go away (as the previous paragraph illustrates perfectly). The war, which has been devastating Ukrainian lands for almost a decade now, has only reinforced the belief that the nearest neighbours will be the ones with whom we will have to defend 'our freedom and yours', as the rebels of the 19th century were fond of repeating. But our nearest neighbours are also those against whom we may together have to defend ourselves (after all, all the Baltic States and Poland share a direct border with Russia and with Belarus, which is sinking deeper and deeper under its influence).

Warsaw’s Museums

Pic 1: An exhibition in the Polish History Museum in Warsaw - a car from Mariupol, Ukraine, riddled with bullet holes

The new Museum of Polish History is located in the Citadel, a military fortress built in Warsaw at Russia’s instigation after the November Uprising in 1830. The Museum, which was opened to the public in September 2023, is a reminder that, ‘what is happening today will be history in the future’. As we read these words in the temporary exhibition space, we are greeted by parts of a car from Mariupol, Ukraine, riddled with bullets. This brutal attack on Ukraine seems to have united our societies, something which did not happen between the wars. There is a great deal of support for Ukraine in both countries, in spite of the differing positions on certain issues (such as the export of Ukrainian goods, which is what Lithuania would like to see to offset the decline in the volume of cargo in the Klaipėda port, but which is currently causing a blockade of the Polish-Ukrainian border).

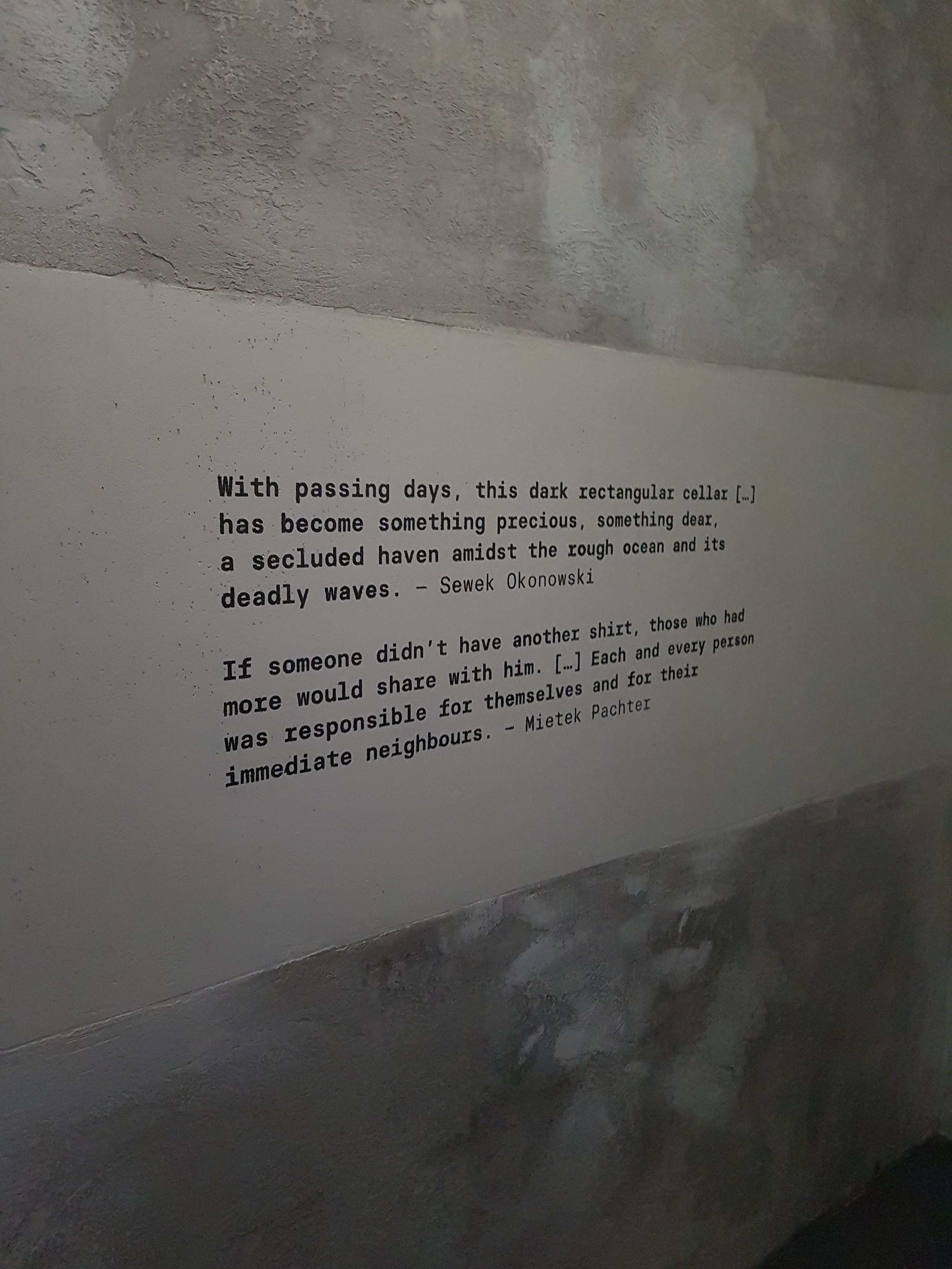

Pic 2: Graffiti in the central part of Warsaw

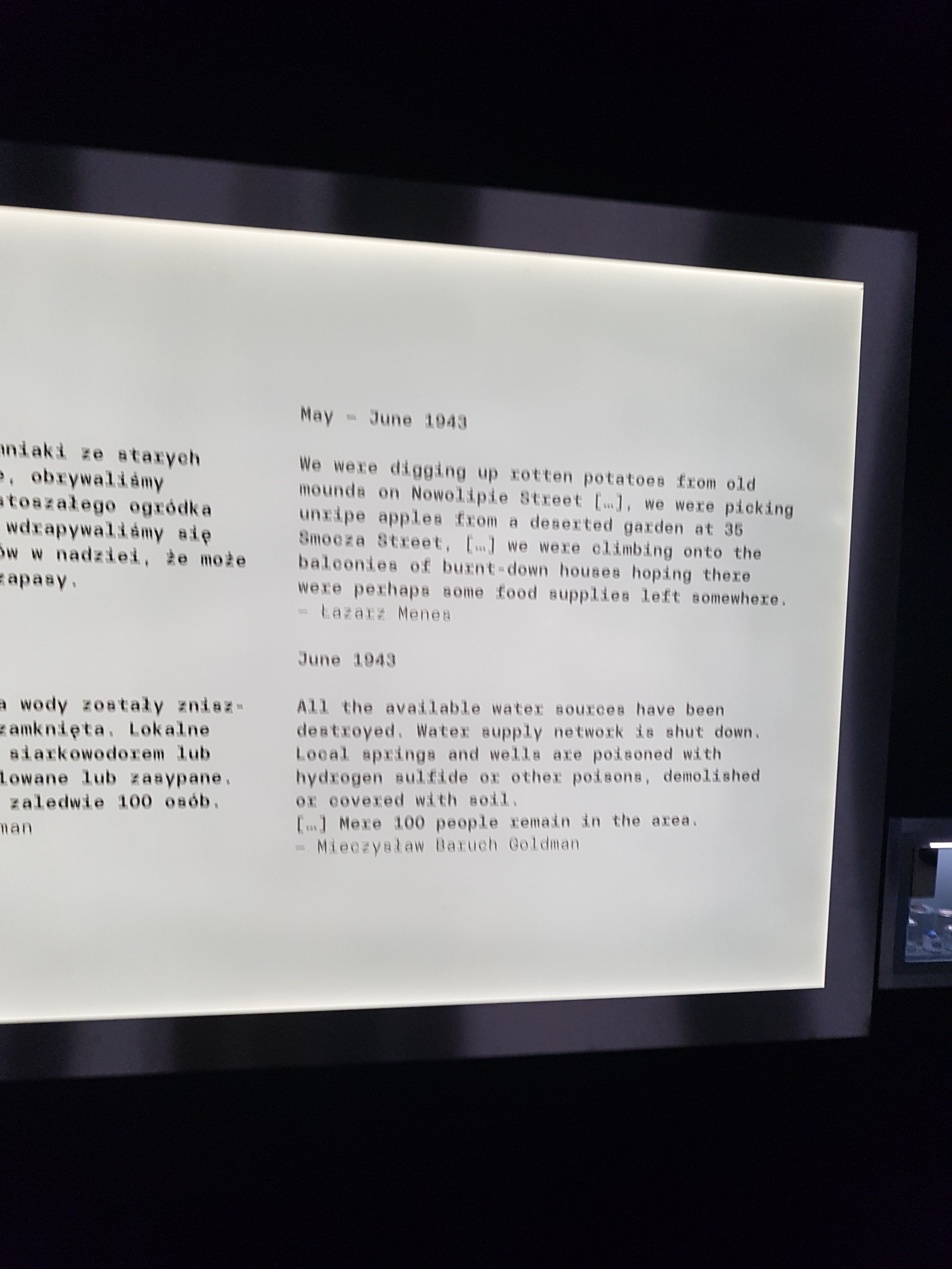

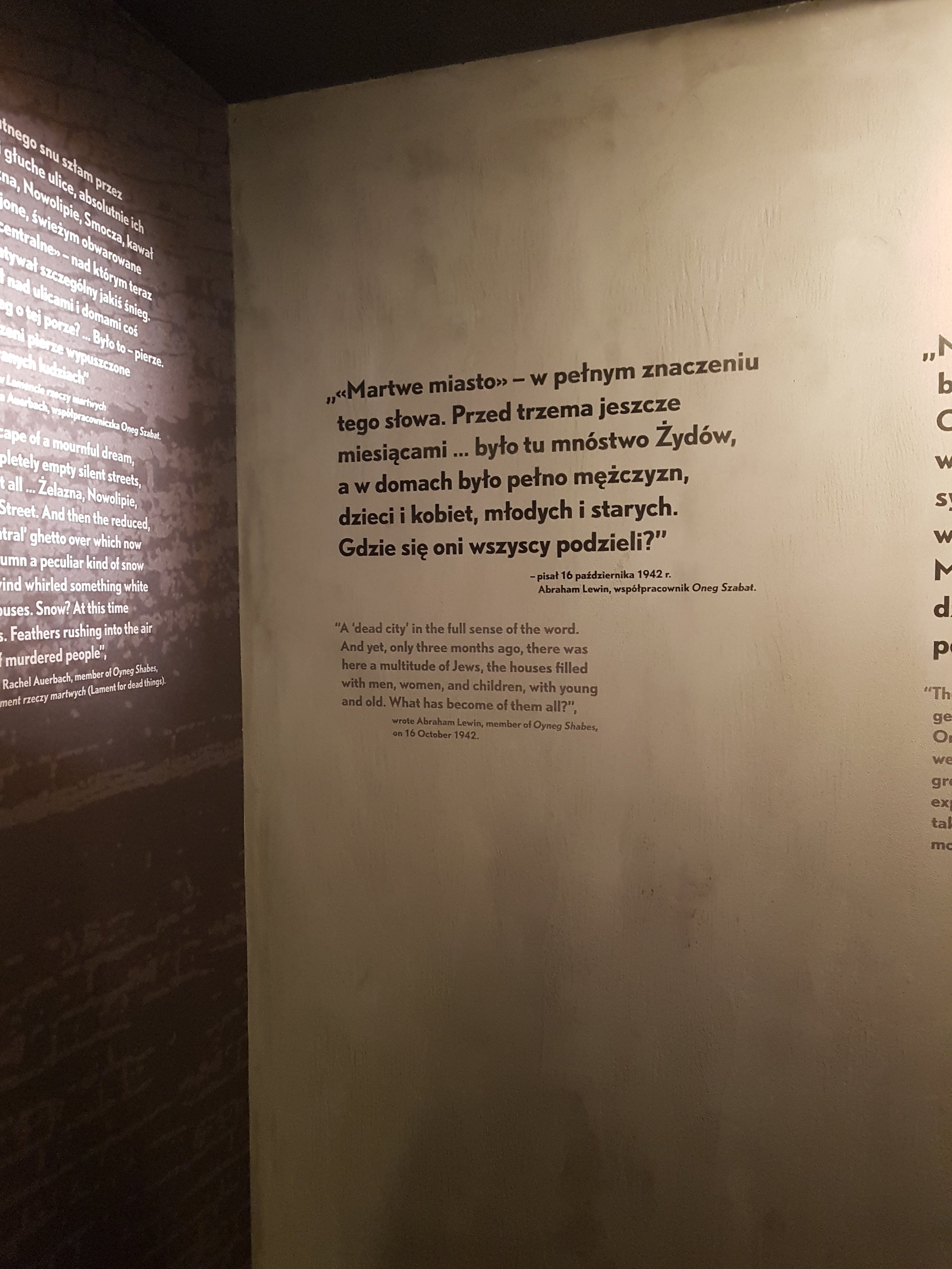

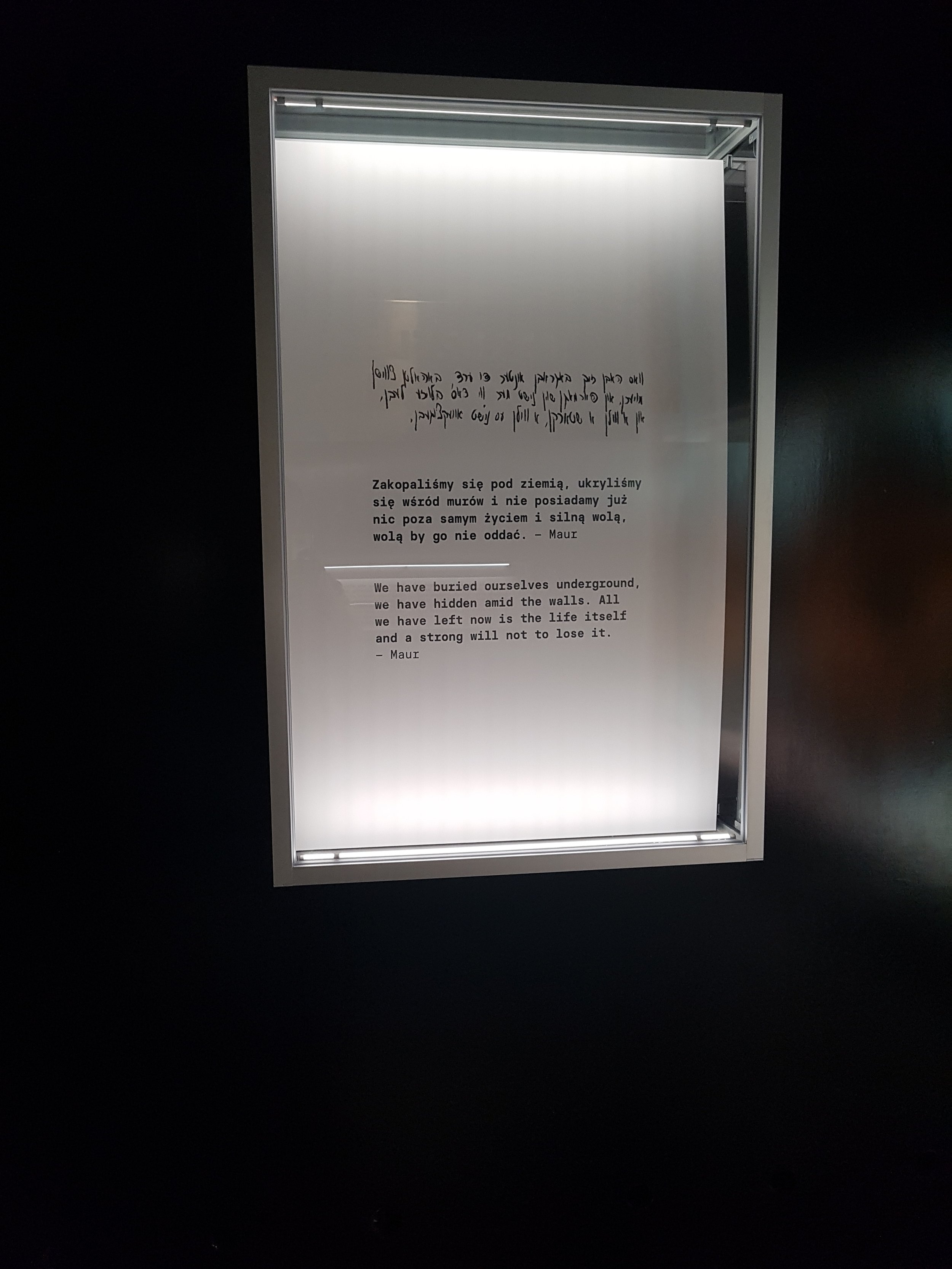

While the attack on Ukraine is by no means the only military conflict ongoing right now, a visit to another of Warsaw's museums proved the most thought-provoking with parallels to another current conflict. This was a visit to the Polin Museum, which, alongside the rich millennial history of Jews in Poland, also presents the painful events of the 20th century. What is happening in the Gaza Strip now, is what I associate most with the ghettos. Although in hellish conditions, people from eastern and southern Ukraine have been able to leave conflict areas. We have also seen in photographs crowds of Armenians leaving Nagorno-Karabakh, but where can the prisoners of the ghettos that cover the 'bloody lands' (as Tymothy Snider has called our lands) retreat to, and where can the people of the Gaza Strip retreat? To a blindly guarded border that they are not allowed to cross? Do the stories of suffering, death, disease and hunger that reach us from the Warsaw ghetto not resemble what is happening today in Gaza? The scale of the destruction, the alerting of international organizations to the humanitarian emergency in terms of lack of food, water, medicine and fuel, is unwittingly correlated with what is being noted in the quotations photographed [see below].

Without questioning Israel's right to defend itself and the fact that Hamas militants must be held accountable for their crimes, can we imagine how this can be achieved without spilling rivers of blood? In the Lithuanian public sphere, such voices are like a cry in the wilderness (perhaps the most widespread questioning of the Israeli actions that are pushing Israel into this situation are the articles by Kęstutis Girnius on Delfi.lt). We can do a thought experiment… based on the thought process of some experts, we should argue that the mass deportation of Lithuanians to Siberia must have benefited the Lithuanian partisans, because it gave additional legitimacy to their struggle. I do not think that such a thesis would find much support in Lithuania today.

Pic 4: The poster for the exhibition Reflection in the Warsaw Rising Museum

A visit to another famous museum in Warsaw - the Warsaw Uprising Museum - allows us to see the installation "Reflection", which asks what you would do in this wartime situation (although the installation talks about taking steps such as taking part in the Uprising). The installation speaks about the determination of our great-grandparents' and grandparents' generation to take up the armed struggle. This question can be turned in another direction: does the fact that some of our grandparents and great-grandparents accepted the suffering and fate of their neighbours who were condemned to death not oblige us to do otherwise?

The words I heard at the Polin Museum about what happens when discrimination against one group of people is dealt with bit by bit were very powerful. It reminds us that "Auschwitz did not fall from the sky", but was approached so gradually that some people at the time did not have any deep doubts about it. From this story we learn what can happen when discrimination against one group of citizens is quietly accepted. I thought that the exhibition 'Around us a sea of fire' at the Polin Museum, which tells the story of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from a civilian perspective, further confirms my choice to see the parallels between what was happening in the ghetto in Warsaw (and not only in the Warsaw Ghetto), and what is happening now. However, what is most disturbing is that this knowledge, this historical experience, although it is known, recalled and remembered, has little impact on our public sphere - most of the time, such texts appear in media outlets whose readers are already aware of it, but how do we reach the hearts and minds of those who, when they hear about what is happening in the world, still only manage to say 'that's the way it is'.

Tadas Šaulys – assistant in the Institute of Grand Duchy of Lithuania. PhD student at Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of History. Historian at Kretinga Museum. Scientific interests: History of interwar Lithuania, role of intellectual elite in public space in interwar Lithuania. E-mail: tadas.saulys@vdu.lt